Chanel Les Exclusifs Eau de Cologne (2007): Recalling Exotic Chanel {Perfume Review}

Eau de Cologne by Guerlain is part of the perfumed library, on trend with the "niche" concept which appeared in 2007, Les Exclusifs. I wrote at the time that this perfume could be considered to have been one destined to be an interpretation of freshness together with Bel Respiro in the collection conceived of as a wardrobe. More than three years later while smelling this eau de cologne more up close I have to say that I am more struck by the duality found in this composition and by its manifest desire to kick some social conventions to the curb instead of seeing it as just a reenactment of the grand genre of the 18th century eau de Cologne however put in more minimalist linguo.

Eau de Cologne by Guerlain is part of the perfumed library, on trend with the "niche" concept which appeared in 2007, Les Exclusifs. I wrote at the time that this perfume could be considered to have been one destined to be an interpretation of freshness together with Bel Respiro in the collection conceived of as a wardrobe. More than three years later while smelling this eau de cologne more up close I have to say that I am more struck by the duality found in this composition and by its manifest desire to kick some social conventions to the curb instead of seeing it as just a reenactment of the grand genre of the 18th century eau de Cologne however put in more minimalist linguo. Behind this composition, we are told at Chanel is an original formulation from 1929 approved by the Grande Mademoiselle herself, she who precisely bore a surname which was once a title used during the Grand Siècle of Louis XIV but which covered a more complex biographical history as several recent cinematographical adaptations of her life have revealed to a wider audience recently. Likewise, this eau de Cologne which one expects to be of the Grand Siècle is less classical than it appears to be.

Elegance here is matched for me with the more unpredictable itinerary of the adventuress or the irregular one as she was nicknamed by biographer Edmonde Charles-Roux who had, truth be told, a tendency to want to try to pigeon-hole her and explain her thanks to social determinism while failing to do so in the end. Indeed, she tells us, how do you explain this quasi Marian mystery, the fact that a descendant of poor peasants from the Auvergne region, itinerant ones at that - near hillbillies, in short - could not go on to have her feet deep in the same ancestral muck? To read the book - which I was not able to finish for the moment being - is to read the story of Chanel, the peasant and the genius, seen through the lenses of someone who holds the prejudiced view that this kind of things could only be a sociological miracle and likes to remind the reader incessantly that Coco smells of something else than the No.5, of smells situated somewhere on the olfactory spectrum ranging from cattle dung to courtesan...

Notes: neroli, bergamot, petitgrain, herbs, spices

The Eau de Cologne by Chanel composed by Jacques Polge, and perhaps Christopher Sheldrake too, opens on a mixed impression mingling the accords of an almost medicinal white cologne with that of very citrusy and juicy Mediterranean fruits. The sensations of freshness and exuberance which are typical of an eau de Cologne - it often replaced water in old-fashioned toilet rituals - are present in the head notes but rendered more discreet and suave, in the register of a conversation held in polite voices in a living room where noises are habitually sunk into a very high quality carpet; the iris that one can smell better in the depth of the composition contributes as usual its patrician feeling of elegance suggestive of a murmur more than resounding laughters pealing at the foot of a fountain where washerwomen gather.

A woodsy note of cedar appears behind this fresh opening recalling at this stage the Eau de Cologne by Thierry Mugler (2001) composed by Alberto Morillas, a reference modern cologne as I realize more and more as I discover its numerous descendants.

A third key tonality escapes from the composition, that of a black cumin/carvi note bringing its ambiguous scent of human skin perspiring with heat and emotion under the sun of the Tropics. One thinks at this point of Eau d'Hermès composed by Edmond Roudnitska, a perfume which could lure you into thinking it is light going by its name only but which is in reality a fiery water, sensual, evocative oh-so-much of immodest flesh. As a matter of course, I also think and perhaps even more so, of the way the cumin note was treated in Kingdom by Alexander McQueen (2003) signed by Jacques Cavallier, a perfume also well-known for its note of rumpled sheets.

I remember reading or perhaps seeing a picture of perfumer Jacques Polge working by his blotters and next to a tray carrying the market's latest launches. The Chanel nose readily confesses not to work in a vacuum nor to rely on field trips to the countryside frequented by the Impressionists, but to look for inspiration in the fragrances themselves. In the book by perfume historian Annick Le Guérer Le parfum des origines à nos jours (Perfume, from its origins to the present day) one even finds a quote which explains this conscious genealogical approach very explicitly. Thus, Jacques Polge when he explains what French perfumery is about by contrast with the American one interprets the first as being more willingly obedient to tradition and perhaps even, one might gather, one which feels it was entrusted with the duty to transmit a patrimonial heritage. Hence - and here I am quickly summarizing his position - "To create something new in perfumery, you must have integrated what exists already."

The Eau de Cologne by Chanel is in my view exemplary of this reflective approach: it seems to offer first its beautiful charms, that is its natural ingredients of high quality for which Chanel is famous in the beginning of the development, then thinking further it borrows from the musky and diffusive cologne by Mugler and finally, it counterbalances this clean white musk note with the more carnal note of rubbing of bodies as of to pay an obligatory homage to Gallic sensuality.

These wefts are weaved to end up offering an eau de Cologne which is subtle but not ethereal, with dry but also rounder fruity notes, and which is both elegant and a bit reckless. This could be the perfume of an English lady in a novel by Agatha Christie where a murder needs to be solved in the shades of white capelines and the immaculate sails of a yacht gliding slowly down the Nile.

Therefore, I see it less as a Grand Siècle cologne than an exotic, spicy one, a little mysterious due to its discreet tonalities, both solar and luxuriously calm. It smells not so much of the neroli of the gardens of Versailles than it ends up evoking a hotel room in a tropical country, heavy with still air, barely shaken by a lazy and indifferent ceiling fan, a scene which represents the fist stage in the disorientation of the senses and life in an adventure story. The fact that one leaves the living rooms of the rue Cambon to find oneself in Le salaire de la peur or in Death on the Nile, or in a spice market, or at least that an ambivalence can be felt by the nose is not surprising in my view if we take into account the fact that the original formula was supervised by Chanel herself. The realistic hardness - Vionnet offered chairs to her workers, Chanel, stools - social adventurism, and even her past of great mistress, if not of high-profile concubine, of rich and influential men is part of her history. The spirit of creativity and vision of Chanel are themselves less reducible but at least one cannot be surprised to perceive blatant sensuality as well as an element of prosaism - a whiff of the anti-clean, anti-soap here, although she had adamantly wanted to integrate the smell of soap into the No.5 - in an Eau de Cologne authentically signed by well-lived Chanel.

One can ask oneself also whether the Grande Mademoiselle dreamt of the Tropics, of a hot breath of air on her skin, of high-temperature shade. Her love for gardenia, her fetish flower, could point in that direction, at once full of elegance and exotic languor incompletely fulfilled. Names of Chanel perfumes like Bois des Iles, Sycomore, Gardenia, Coromandel and Chanel's iconic taste for Chinese lacquered windscreens are like vistas onto the discreet tradition of exoticism at Chanel.

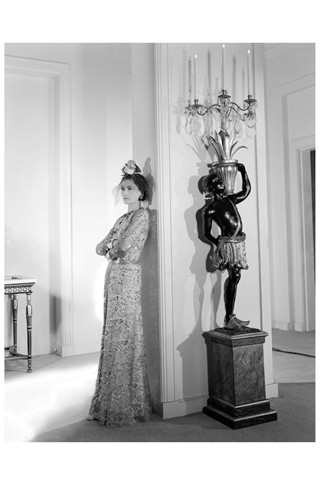

Photo: Life Magazine