Chandler Burr Untitled Series S01E0: A New Experiment in Unadulterated Olfactory Perception: Synergists could Rebel {Scented Thoughts}

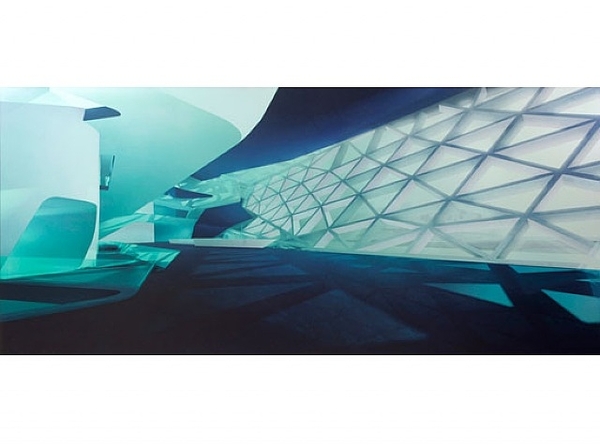

Guang-Zhou Opera House by Zaha Hadid, 2006

Guang-Zhou Opera House by Zaha Hadid, 2006

Scent critic Chandler Burr has long been fascinated by the possibility to arrive at a pure apprehension of the olfactory form separate from its usual trappings: name, container, story-telling, advertising imagery, color. Is it a necessary prerequisite for the curator of olfactory art at the Museum of Art and Design in New York City to demonstrate that there is an art of olfaction which is distinct from others?

He has launched a smell experiment aimed at 100 willing guinea pigs each month. It's more expensive than with Birch Box but it promises an education in the art of correct smelling of perfumes, not just of testing of commercial market products. He is trying to sell the idea that perfume is art, not just a vulgar appendage to publicity-seeking and money-grabbing brands. This is done in association with a market place...

One thing he is already demonstrating from the outset is that suppress the external costs and the price of a juice can be democratized at $50 for 50 ml of scent speculation that will last you for a month. Unless you recognize the perfume bought blind immediately.

One may wonder whether his target audience of perfume aficions restricted to an elite 100 are really the ones who need his guidance most. His project sounds like a terrific fit, with some amendments, for primary schoolers. Will the occasional scent purchaser feel compelled to entrust their theoretical need for scent direction to this program? 100 participants are not statistically significant. The bottles have reportedly sold out quickly, yes, all 100 of them.

But of course, you have to take Burr's proposition seriously to see if it works. The question his purist stance raises is to ask oneself whether to demonstrate that perfume is art we need to essentialize it that starkly?

Take, for instance, the art of opera singing. To appreciate it in full, a purist might say, or an opera music critic might decide to conduct an experiment whereby the singing would take place in a desert or a vast airplane garage; opera singers would be naked and spectators would have forgotten their general musical education in order to try not to identity the notes too quickly nor too stereotypically.

Opera, like perfume, relishes on a host of "external" trappings to the art of singing itself. But looking at the distinctions of essential and non-essential or internal/external may bring to light the fact that opera art precisely plays upon an appropriation of these "externals" to come and enrich its core medium of expression, singing.

Opera is this idea that there can be a form of singing which is not just about voice, but action and acting, the aesthetics of a place, stories, drama. Some opera trappings might be discarded occasionally but mostly opera takes place in an opera house. It even becomes the pretext for elegant fashion parades to look forward to on the part of spectators who participate in this way to that art like perfume lovers might wear fragrance to identify with its message of elegance; operas are traditionally staged within a "container"; there is a decor; there is a house. The architecture is not just mere anecdote as through the science of acoustics, it plays a fundamental role in supporting music and human voice. Spectators know what they are going to listen to and watch; the opera has a title, a narrative. They know the names of the singers and expect a certain level of performance. Opera is both musicality and visuality united by dramaturgy.

Who could potentially be interested in deconstructing opera saying it ought to be in essence about the singing only? There can logically be this temptation because it is the most essential part of this art. Mute the music, and a singer could still sing; the orchestra adds something to the singing which comes second place in feeling essential. Next, put the singers in potato sacks, transform the stage into an industrial loft and La Traviata will continue to be sung and performed, no problem. Of course, you the spectator can sit in the opera house and decide to close your eyes to filter out the unnecessary visual details. But does an opera-goer really want to do that? Do they want to forego the spectacle of the opera? Is she or he a better connoisseur of singing for electing to do so?

Chandler Burr's position, if we understand it correctly, cannot be to revolutionize our way of peceiving scent by discarding its historical companions: flacon, images, spokespersons dramatizing the scent, etc. but to conduct an experiment to help a prospective audience not to confuse visual cues with olfactory ones since the sense of sight is so dominant in our cultures. It is an attempt to give higher status to the sense of smell by emancipating it from vision. Going back to the opera example, an opera lover can listen to opera on a CD at home, in the dark, if she or he wishes to do so. A perfume lover can do the same, casually. But what is at stake here for perfume appreciation as defined by a scent critic is to decide that all visual clues are in a way "anti-olfaction", that they would work against our authentic apprehension of scent; they are, according to this view, a distraction from the essential.

This is partly true. You do smell better the more you focus on the perfume itself. Having less visual stimuli helps although in fact you do tend to become more and more able to dissociate the two. I put on Alcina "Ah! Mio Cor!" sung by Magdalena Kozena and try to see the difference between blind and open-eye listening. It is two types of experience, not just one of them is truer. Blind listening is perhaps more empathic. Open-eyed listening is perhaps more condusive to rêverie and the insertion of music in the goings of life.

Rather than Chandler Burr's negativist approach though, we think that it is more essential to smell a lot, in every situation, to smell on a regular basis so that you construct for yourself a culture of scent, the one whose language runs invisible under the labels. Soon, you will be able to smell the patterns, the classic accords, the twists on the classic accords, the stereotypes, the copies etc. It is through habit that you form judgement. Within the span of the one month that you will be pondering on S01E0, you could have smelled many perfumes high and low.

So, as a scent critic, Burr is perhaps saying also that he is pre-selecting for you the best of the best, so that you will be educated in the contemplation of perfume masterpieces albeit in a more abstract way than is usual. But this is quite easily done at home. Do some research, pre-select for yourself 20 must-smell perfumes. Pour them into lab samples - trying to ignore the clinical connotation so that it does not influence your perception - remix or ask a friend to redistribute them, then smell them for yourself during the course of time needed to feel you have wrapped your mind around a scent.

There is something attractive in this idea of being guided in your perfume contemplation. Its special rhythm ensures a different type of experience, if it is adhered to. But mostly, the project is bound to attract most people who just want to add a new layer to their multiform approach to perfume appreciation.

Finally, there is on a more philosophical plane the problem that perfumers themselves use "external" tools to create their perfumes. It might be words, images, colors, stories. Even when invisible, these non-purely ofactory events are contained de facto in the perfume, which is a very psychological and intuitive form of art when it is authentic creation and not just a rehash - this you can feel too.

Sophia Grojsman recounted once how shocked she was to hear blind testers speak of a dark-haired, red-lipped woman in a fur coat on Red Place in Moscow when they smelled Trésor, which was the imaginings she had put into the scent. How will a purist then be able to excise "internal imagery" to perfume from it? What is the "correct" language to talk about perfume since it has been formed so much with vocabulary dominated by the visual sense? Do we really need an olfactory art stripped stark naked of its cultural references? The paradox with this Untitled Series is that it may feel the most gimmicky to those who are the best candidates for this project; the juice better be really worthwhile for the money value.

One aspect of perfumery that contributes to perfume being an interesting sensorial object is that like opera, it operates with synergy. This creates a new level of creative difficulty. Imagine a great perfume which is not just a great juice but a great synergy, at all levels of the object called "perfume". A higher form of artistic synergy rather than jus commercial synergy thus, it can be argued, can also be cultivated to make perfumery a more total art form.