The Story of the Royal Anointing Oil in England: From the Sacred to the Fragrant {Perfume History & Facts}

The Royal English ampulla and anointing spoon, Royal Exhibitions

Following the British pomp and pageantry on TV on the occasion of the Diamond Jubilee of Elizabeth II is a wonderful distraction, especially for those who even without being royalists, can appreciate the import of traditions. For perfumophiles, it is a good opportunity to pause on an almost closed chapter of perfumed history, little known in its detail at least, although everyone almost must have heard of the sacred anointing oil which consecrates a newly enthroned sovereign. This oil is not simply an oleaginous body but contains aromatic ingredients and is in fact a perfume oil.

60 years ago, the new Elizabeth II, like her forebears, received the unction of that sacred oil, which is perfumed following a precise recipe which if we are to adhere to a longer historical framework, goes back to the Mesopotamians, the Egyptians and in the Biblical tradition, to Moses. We shall not go back as far in time, or only just for a few moments, to point out the linkage and the fact that some ingredients have been kept, but most have been changed...

Antiquity Roots for the Anointing Oil

In the Dictionnaire universel des sciences ecclésiastiques by Jean-Baptiste Glaire published in 1868, the author gives a recipe for the original anointing oil which is said to have been created by Moses receiving dictation from God to consecrate kings and priests but also the vases and instruments used by Jews in the Tabernacle and then in the Temple. In it, we find myrrh, cinnamon, "aromatic reed" and olive oil, "the whole blended according to the art of the perfumers". It is a reference to a passage in Exodus 30: 22-25 where a more complete recipe is provided.

"Then the Lord said to Moses, "Take the followng fine spices: 500 shekels of liquid myrrh, half as much (that is, 250 shekels) of fragrant cinnamon, 250 shekels of fragrant cane, 500 shekels of Cassia - all according to the sanctuary shekel - and a hin of olive oil. Make these into a sacred anointing oil, a fragrant blend, the work of a perfumer. It will be the sacred anointing oil."

The fact that "the work of a perfumer" is specified and required means that the anointing oil was not just a sacred symbolic blend but one needing the mastery of a nose and his sense of aesthetic balance in order for it to smell delightful. It was thus also meant to convey sacredness through the experience of a pleasant sensual smell. A perfumer would have been able to source adequate ingredients and re-equilibrate the formula so that the whole would be fragrant, not just potent.

One of the fascinating aspect of the history and story of the anointing oil is that the sacredness of the holy oil put a constraint on it to retain its material integrity over the centuries and be destined to future generations, as it is. Ideally, it would have to remain that very blend which was originally created. But with accidents of history taking place, this ideal of eternity contained in the creation of the oil is tested. Hence, it can be "destroyed" and then needs to be recreated as faithfully as possible. In some other instances, the oil has been preserved but only a dried bit remains, so that pain is taken to transfer if only a drop or a particule on the head of a pin from the ancient anointing oil to the new one.

In the story of the royal English anointing oil we see recurring patterns of meaning even when change is introduced.

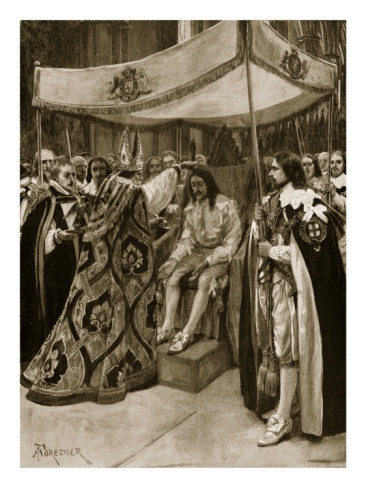

The Anointing Oil Commissioned by Charles I

The Anointing Oil Commissioned by Charles I

In Cursing the Basil and Other Folklore of the Garden (1998), Vivian A. Rich, recounts that on the eve of the coronation of Mary I in 1553, 400 years to a year before that of Elizabeth II, the future sovereign thought that the remaining chrism oil having served for the coronation of Edward VI, her half-brother, could not be used because he was a Protestant and she a Catholic. She "was afraid that the oil had lost its potency in the hands of Protestant bishops" writes Rich. For this reason, she turned to the Catholic bishop of Arras in present-day Belgium to have a newly consecrated oil be made.

Elizabeth I is reported to be the first one to have discarded religious considerations and applied aesthetic judgment to the sacred anointing oil finding it to be greasy and foul-smelling. She is reported to have berated her ladies in waiting shortly after the ceremony had taken place, and after having retreated behind a curtain telling them "Away with you, the oil is stinking".

It befell Charles I to custom order a new, more fragrant anointing oil to be used at his own coronation in 1626. It is this 17th century recipe which is the one which is closest to the one which was used for Elizabeth II in June 1953. The anointing oil of Charles I newly included wafts of orange blossoms, roses, cinnamon, jasmine, musk, civet and ambergris. It reveals the more layman taste of the period for floral and animalic notes. While the anoining oil is sacred, this modern iteration has a foot firmly planted in the hedonistic pleasures of the earth sounding less austere than more antique recipes.

Elizabeth II being shown the ampulla and anointing spoon in 2012 together with a delegation representing world religions via

Elizabeth II being shown the ampulla and anointing spoon in 2012 together with a delegation representing world religions via

How the Anointing Oil was Made, Lost and Reclaimed

The author of this recipe is known. He was an émigré Swiss doctor, Theodore de Mayerne, a Huguenot doctor deeply interested in chemical medicine. The anoining oil was compounded by the royal apothecary, another Huguenot, Nicholas le Myre. Mayerne's recipe now included orange blossoms and jasmine blossoms distilled in Benjamin oil - another name is "Ben oil"- rose, cinnamon, benzoin, ambergris, musk, civet and spirit of Rosemary.

It was also made in batches large enough with the intention to have the anointing oil last for several coronations. It reportedly lasted until the coronation of Queen Victoria although it is said elsewhere to have been prepared by Squire & Sons in 1837. Due to her exceptionally long reign, it had to be made afresh for her son, Edward VII as the oil had coagulated. George V used the same oil in 1911. A second fresh batch was made from this Charles I recipe for Edward VIII but following his abdication was used by George VI in 1937 instead.

When the turn of Elizabeth II came in 1953, it was discovered that while sufficient quantity would have remained from the anointing oil used for her father, it had been destroyed during the London raids of WWII in May of 1941 when it was kept in the deanery of Westminster Abbey. Then the company who made it, Squire & Sons, had gone out of business so that in the end the saviour of the day turned out to be an old retired employee who had kept some of the anointing oil as a souvenir according to one account. According to another account, the grand-daughter of Peter Squire had kept the recipe. It was analyzed and reconstituted by a chemist, J.D. Jamieson of Savory & Moore Ltd, which had taken over Squire & Sons company. The formula used on the coronation day of Elizabeth II which was prepared by the Surgeon-Apothecary lists the ingredients of neroli, jasmine, rose, cinnamon, benzoin, musk, civet and ambergris. A change is noted where the type of oil is concerned, not longer "oil of been" (oil of Ben) as for Charles I, but sesame oil. The oil was then consecrated by the bishop fo Gloucester in the chapel of St. Edward the Confessor.

When the turn of Elizabeth II came in 1953, it was discovered that while sufficient quantity would have remained from the anointing oil used for her father, it had been destroyed during the London raids of WWII in May of 1941 when it was kept in the deanery of Westminster Abbey. Then the company who made it, Squire & Sons, had gone out of business so that in the end the saviour of the day turned out to be an old retired employee who had kept some of the anointing oil as a souvenir according to one account. According to another account, the grand-daughter of Peter Squire had kept the recipe. It was analyzed and reconstituted by a chemist, J.D. Jamieson of Savory & Moore Ltd, which had taken over Squire & Sons company. The formula used on the coronation day of Elizabeth II which was prepared by the Surgeon-Apothecary lists the ingredients of neroli, jasmine, rose, cinnamon, benzoin, musk, civet and ambergris. A change is noted where the type of oil is concerned, not longer "oil of been" (oil of Ben) as for Charles I, but sesame oil. The oil was then consecrated by the bishop fo Gloucester in the chapel of St. Edward the Confessor.

The gesture of anointing the sovereign can differ. For Charles I, the king was anointed on the breast, between the shoulders, on both shoulders, in the crooks of both arms and on the head. For Elizabeth II, the queen was anointed on the palms of her hands, her breast and her head.

The Secularization of the Holy Anointing Oil

From a perfumery perspective, one can note that a single ingredient remains throughout from bibilical times, cinnamon, while it seems that myrrh is not cited anymore despite its religious connotations. In modern times, benzoin seems to replace it although "myrrh" could have alluded to a blend of resins, which would have very possibly comprised benzoin.

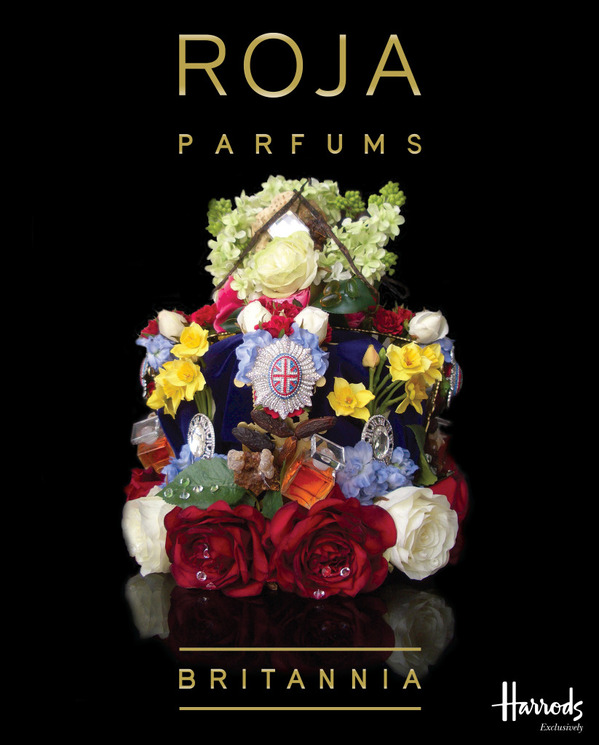

The oil evolved from a sacred liturgical scent to a more elaborate formula created with the idea of pleasing the nose and smelling pleasant to men, Charles I in particular. Today, the progress in the realm of secularist perfumery has been taken a step further with Roja Dove who created a limited-edition perfume inspired by the holy anointing oil called "Britannia". It is edited at 60 exclusive copies for Harrods. It is described as "Roja's personal interpretation for a majestic perfume, a serenely tailored creation filled with perfectly balanced noble ingredients: the Rose, symbol of England; Jasmine, the Queen of flowers; and anointing oils of Her Majesty." In the list of ingredients provided as being that of the anointing oil serving as inspiration, a new fruity note appears, "orange", although they might have simply forgotten to write "blossom". But still, no "myrrh". And yes, finally, the holy anointing oil is being discussed on a perfume blog. How much more democratic and secular could it get than that?

The oil evolved from a sacred liturgical scent to a more elaborate formula created with the idea of pleasing the nose and smelling pleasant to men, Charles I in particular. Today, the progress in the realm of secularist perfumery has been taken a step further with Roja Dove who created a limited-edition perfume inspired by the holy anointing oil called "Britannia". It is edited at 60 exclusive copies for Harrods. It is described as "Roja's personal interpretation for a majestic perfume, a serenely tailored creation filled with perfectly balanced noble ingredients: the Rose, symbol of England; Jasmine, the Queen of flowers; and anointing oils of Her Majesty." In the list of ingredients provided as being that of the anointing oil serving as inspiration, a new fruity note appears, "orange", although they might have simply forgotten to write "blossom". But still, no "myrrh". And yes, finally, the holy anointing oil is being discussed on a perfume blog. How much more democratic and secular could it get than that?

Greetings:

Because of the objection of India to the anointing if the breast as being symbolic of the "Nurture and Admonishion of the catholic Anglican Church", it was necessary to create the "Imperial Crown of State", for the coronation of Queen Victoria; otherwise, there would not have been a "British Empire" with India included; moreover, the "Saint Edward the Confessor" Crown required the three part anointing of Hand [Sword]; Head[Authority], and Breast [Religion]. Right?/dmf

Thank you for these politico-theological explanations. It's quite intricate.